NEIL LEADBEATER Reviews

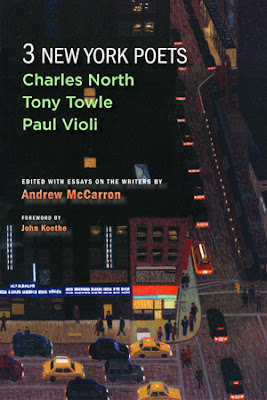

3 New York Poets:Charles North, Tony Towle, Paul Violi edited with essays on the writers by Andrew McCarron

(Station Hill Press, Barrytown, New York, 2015)

In

his Foreword, John Koethe describes this book as a “psychological, biographical

and literary study”—which arose out of a dissertation for which McCarron

received a doctorate in psychology from the Graduate Center of the City

University of New York in 2010. It details the work of three poets associated

with the so-called New York School of Poetry, each of whom has received a

decent amount of recognition but deserves to be more widely known. Koethe makes

the point that, as with the first generation of the New York School of Poetry,

it is their personal and historic connections that draw them together rather

than any particular shared view of poetics given that their work is hard to

characterize and delineate in terms of its content and common purpose.

McCarron,

in his informative introduction, explains how he drew upon sources for his work

(no major biographical work had been undertaken in this area at the time), his

meetings with the three poets and the different circumstances in which they

took place. Sadly, one year after he had defended his dissertation, one of the

poets, Paul Violi, was taken ill quite suddenly and died of aggressive

pancreatic cancer.

The

book is structured in three parts of equal length. Each section contains a

sample of the poets’ work followed by a biographical account of their life as

told through a series of interviews and a literary study of their work. I will cover each section in turn.

*

North’s

work is represented by eleven poems written between the years 1974 and 2013 and

include the long poem “Summer of Living Dangerously” (2007) which is written in

the form of a diary that covers a period of forty-five days in 2001.

Documenting

North’s Jewish-American parentage, Russian on both sides, McCarron traces the

influence that came largely from his mother’s side on North’s early life.

North

speaks with warmth and appreciation of his mother’s musical influence but

candidly alludes to the fact that his feelings towards his parents are

complicated and that he is surprised by just how much of his childhood he has

blotted out over the years.

McCarron

covers all the major turning points of North’s life: his decision not to pursue

a career in music or law, his meeting with his future wife, Paula, his

incursions into academia, graduation and marriage. Returning to New York in

1965, after a short period abroad, McCarron details how North was getting

closer to finding his true vocation. It was John Unterecker, himself a poet,

who suggested that North attend the New School poetry workshop being taught by

Kenneth Koch. After some hesitation, North finally enrolled in the fall of 1966

and the rest, as they say, is history.

I kept putting it off –

probably out of sheer insecurity – but finally did enrol in Kenneth’s poetry

workshop, and it turned out to be the last time that he taught there.

McCarron

charts North’s breakthrough which came in the spring of 1970 when he attended a

poetry workshop offered by Tony Towle at the Poetry Project. Towle encouraged North in his poetic

endeavours and North credits Towle for his enthusiasm and intelligence. It was

here that he also met Paul Violi. The three became lifelong friends.

In a

separate section, McCarron recounts North’s association with James Schuyler. It

was not long before North’s admiration for Schuyler’s work was to be reciprocated,

much to his delight. Of North, Schuyler wrote “His joy in words, and the things

words adumbrate, is infectious: we catch a contagion of enlightenment. To me,

he is the most stimulating poet of his generation.”

Literary

recognition on a greater scale, always a difficult thing to achieve, came to

North late on in his career. In some ways, he was a victim of the poetry

world’s “false reputations” (a phrase possibly picked up from Koch) in which

recognition is based on factors that have little to do with merit. Regrets

aside, North admits that life has been good to him. Marriage to Paula and the

successful upbringing of their two children has clearly been a great source of

pleasure, inspiration and pride.

In the

section on North’s work, we get an insight into his method of composition – I don’t write slowly but I finish slowly – his

interest in the poetics of form with specific reference to his famous line-up

poems and an explanation about the long poem “Building Sixteens.” McCarron

makes the point that the non-confessional nature of North’s work can be

explained in part by his reserve and the fact that he is more interested in how

a poem works rather than what a poem is about. Reference is made to the way in

which music plays a part in his poetry, in particular, the clarinet. In

summary, McCarron considers that North’s work is “an important tributary of

American poetry, and specifically New York School poetry, because it expands

the possibilities of what a poem can be, while simultaneously falling within

the continuum of the American lyrical tradition.”

*

How

much do we, as poets, reveal about ourselves in our writing is an interesting

question. Tony Towle’s poems are described in this book as being autobiographical

even though he has himself said that poetry

for him, was, if not outside of life exactly, only coincidentally

autobiographical. McCarron includes Towle’s long poem Autobiography (1970-1973) among the selection of 12 poems written

between the years 1963 and 2009 as an example of his work.

McCarron

maps the difficulties Towle faced early on in life—his mother died of cancer

relatively young, Towle was separated from his brother and two sisters who were

put into foster care and he had a strained relationship with his father who was

ill-equipped to raise a family after the death of his spouse. Towle’s struggle

with borderline poverty as a young man in New York City is touched upon

together with his struggles with failed relationships, marriage and fatherhood

and the uncertainty of finding any form of permanent employment until he found

work at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), a fine

art print publisher established in 1957 by Tatyana Grosman, which Towle

describes as being at the forefront of the American print renaissance of the

60s and 70s. Towle carved out a niche for himself at ULAE where he found it

inspiring to be around important artists in their working environment. Although

his full-time association with ULAE was over by the middle of 1979 he remained

involved in some of its activities, working on a part-time basis until 1981.

What

comes across in this section is the way in which, despite the difficulties that

he faced in his personal life, poetry was the one constant that kept him going.

McCarron writes of Towle’s appreciation of O’Hara’s work, his regular meetings

with Charles North and Paul Violi, the appreciation of his peers for his own

writing at the St. Mark’s Poetry Project and his long-lasting social relationships

with artist friends and colleagues including Ted Berrigan, David Shapiro, John

Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, James Schuyler and, most importantly, Frank O’Hara. His

girlfriend, Diane, according to Towle, saved his emotional life and gave him

stability in his later years.

In

discussing Towle’s work, McCarron observes how many of the poems feature

mythological and historical figures on difficult life journeys that to some

extent mirror his own questing spirit and the illumination of

self-knowledge. Towle’s meticulous

attention to detail, in particular, the way in which he places his work in

terms of years, dates and seasons, is highlighted. All his poems are carefully

dated together with many of the events that are described within them. The

heart of New York City “saturates” his poems which have “the fast-paced feel of

city traffic: images, perspectives, and tones shifting like street scenery from

the backseat of a yellow cab.” His life work is “the portrait of a man

searching for the still center of a turning world.”

*

Nine

poems dating from 1973 to 2011 are included in the selection representing the

work of Paul Violi chief among which are excerpts from the sequence Further I.D.’s—a contemporary take,

perhaps, on the Anglo-Saxon Riddles prompting the question Who am I? at the end of each sequence. The inclusion of poems such

as Index and Wet Bread and Roasted Pearls illustrate Violi’s flare for

quirkiness and originality.

Reading

about Violi’s early life, his steady upbringing within a loving, supportive and

cohesive family, one cannot help but draw comparison with the contrasting

situation appertaining to Tony Towle. Violi’s parents encouraged his early

interest in poetry and placed a good deal of importance on his education. Violi

studied English and Art History at Boston University from 1962 to 1966. McCarron mentions how the great satirists—Pope,

Swift, Dryden, Voltaire, etc.—played a crucial role at this time in shaping

where Violi’s literary leanings would lie. He charts his love of sports and

everything to do with the outdoor life, his time in the Peace Corps which

included a seven month assignment as a surveyor and mapmaker in Nigeria, much

of which is documented in the form of impressions in his book-length poem Harmatan, followed by a period of travel to France, Greece, Turkey, Iran

and Nepal. On his return to America, he shared the disenchantment of many of

his fellow citizens over Vietnam.

Following

his marriage in 1969 and subsequent fatherhood, McCarron documents Violi’s

foray into the downtown poetry scene, his meetings with Kenneth Koch, Tony

Towle and Charles North; his life in the Hudson Valley where he and his wife

raised their two children, his periods of employment working as a journalist at

The Herald and then as the managing

editor of Architectural Forum followed

by his entrance into teaching—a place where he found his true vocation teaching

literature seminars for the English Department at Columbia University which

included courses on Satire, Modern American Poetry and early twentieth-century

British poetry. After his untimely death, there was an outpouring of affection

from all who knew him. McCarron sums his character up by stating that he was “a

family man and an epic socializer, a gregarious worker and a reclusive writer,

a great humourist and a quiet dreamer.”

In

discussing his work, McCarron observes how Violi found his lasting literary

heroes in the satirists of the early 18th and 19th

centuries and the early modernists. He places particular emphasis on the fact

that humour and absurdity are defining features of his work. He turned the raw

material of everyday life into poetry that was accessible and appealing to

audiences everywhere.

This is

an inspiring book about three very different poets who became close friends. It

is also an excellent introduction to their life and work and will be a welcome

addition for anyone who has an interest in the poetry of the New York School.

*****

Neil Leadbeater is an author, editor,

essayist, poet and critic living in Edinburgh, Scotland. His short stories,

articles and poems have been published widely in anthologies and journals both

at home and abroad. His books include Hoarding

Conkers at Hailes Abbey (Littoral Press, 2010), Librettos for the Black Madonna (White Adder Press, 2011); The Worcester Fragments (Original Plus,

2013); The Loveliest Vein of Our Lives (Poetry

Space, 2014) and Finding the River Horse (Littoral

Press, 2017). His work has been translated into Dutch, Romanian, Spanish and

Swedish.