The poem on page 1

tells us some of what to look for in the rest of the book.

-- Above the poem is

a dedication to Bennett's wife: For Cathy, siempre. (The copyright page faces

page 1, and has as its dedication: For C. Mehrl Bennett, with love always.) In

case any reader might ever think of this book and these poems as some kind of

abstraction or series of formal experiments, Bennett makes it clear from the

outset that his writing is coming directly from his life, from what is most

important to him in his daily life.

-- The dedication is

written in two languages, in English and in Spanish. We should expect to find

more Spanish as we move along in the book, and we should probably expect some

Portuguese, French and Nahuatl as well.

-- The first word in

the poem is salt, spelled "ssalt". We should expect more deliberate

misspellings, of various sorts, employed for various reasons. In this poem,

salt is misspelled as the first and last word in the first line. As the last

word, it is spelled "saltt".

The length of the

first line here has been determined by the fourth line, the line in which the

title -- letter -- appears, surrounded by mazesalt and saltmaze:

mazesaltlettersaltmaze

The first word in the

poem, as it is intended to be read, is not the first word in the poem as it is

intended to be seen.

The first word in the

poem is the word "salt" or "saltmaze" as it appears

following the word "letter", in bold face, which is the title.

The word

"letter" has six letters, in contrast to both "salt" and

"maze", which have four. In order to have the poem appear as a

"block", every line has to cover the same "amount of em

space". The first written line consists of the last two words of the poem

-- maze salt -- and the first two, salt maze, plus the title, letter.

The first line

beneath the title begins with salt, and requires an additional 's' at the

beginning and 't' at the end to be exactly as long visually as the line which

includes the title. The next line begins with maze, and does not require any

additional letters, because it has three instances of the word

"maze", as contrasted with two in the previous line, and the added

instances of the letters 'm' and 'z' in "maze" are equal spatially to

the additional 's' and 't' in the previous line. The third line here is the

same as the first. It is followed by a line made up of the single word

"eye", in boldface.

The title of the

poem, then, is "letter eye", for reasons which are becoming

increasingly clear.

Following the

single-word line "eye", which occupies the center of the poem as it

is intended to be read, but the end of the poem as it is intended to be seen,

we return to the top of the "block", and begin reading the second

half of the poem (it is a seven-line poem as I see it, as I look at it, but the

more I read it -- and think about reading it -- the less satisfactory

identifying it as having seven lines becomes. Maybe it is an eight-line poem,

with the title-line serving as both the first and the last line. That makes

sense visually, but I can't actually read it that way. As far as reading -- not

looking -- is concerned, line one must be a two-word line -- salt maze --

followed by three four-word lines -- all words in the poem having no spaces

between them -- followed by a one-word line -- I had not thought of this as a

"line" until now -- followed by three four-word lines and the final

two-word line preceding the title).

So, the shape of the

poem in our reading of it, which is invisible unless the form of the poem as a

"block" is utterly destroyed, is as follows:

letter

For Cathy,

siempre

saltmaze

ssaltmazesaltmazesaltt mazesaltmazesaltmaze ssaltmazesaltmazesaltt

eye

ssaltmazesaltmazesaltt

mazesaltmazesaltmaze

ssaltmazesaltmazesaltt maze salt

-- A postscript

informs us that the poem was "found in Ivan Arguelles 'archaic'. We should

expect more findings in, distillations of, and extractions from the works of

other poets and writers, both those, like Arguelles, who are friends and

contemporaries of Bennett, and others who are historical figures. We might also

keep an eye out for other instances of the archaic.

The first poem on

page two opens with the phrase "sample of a clue". Is this one clue

among many, or a part of a single clue? It is both. It is the first line in a

seven-line "block" poem. I flip quickly through the book and find a

lot of seven-line poems. Across the crease is an eight-line "block

poem". I flip quickly through the book and find a lot of eight-line poems.

"you break /

your tooth the street nnnn / shitless churns a stunner."

Here the clues

are

1) "break" refers immediately to "line break" and then

to "your tooth" (poems in this book will refer to themselves, to

their forms and formal components)

2) the four 'n's, in bold face, signify only

their own shapes and sounds, which will be repeated as an end rhyme with

"stunner" in the next line

Next:

"soap of

chins and cost re

tainment no"

"my sawdust

wind

or soup's a hand"

"ch

ew or

mumbling in the lint"

Four lines here,

shown as six, are meant to emphasize one possible rhythmic pattern, hidden in

the block form. These three rhythmic units work against the rhythmic clues

given by the block-shape of the poem. We are not interpreting any kind of

graphic score here, this is not a visual poem which guides us through its

soundings. This is a visual form designed precisely to work against its

rhythmic patterns.

The first line

actually provides us with a clue about how to read it, thereby giving us a clue

about how to read what follows. There is an extra space between "you' and

"break":

sample of a clue you

break

That break, which

precedes the word "break", is a rhythmic marker. The next rhythmic

unit is

"break your

tooth the street nnnn"

followed by

"shitless churns

a stunner" [where line = rhythmic unit, perhaps the only instance of that

in this poem]

Alternatively, the

first two lines can be read as uniquely irregular in this otherwise

rhythmically consistent poem, where line coincides with rhythmic unit in lines

3, 4, 5 and 6, and possibly even 7, though the extra space in line seven

between "mumbling" and "in the lint" cause us to question

the stability and persistence of any choice of rhythmic patterns for our

reading. Once we attend to this final added space, we notice that there are

extra spaces throughout the poem:

in line three,

between "shitless" and "churns", between "churns"

and "a", and also between "a" and "stunner (so we

might read it as "shitless" pause "churns" pause

"a" pause stunner";

the same

configuration in line four: the first word "soap" followed by two

spaces, then the second word "of" followed by two spaces, and then

the phrase "and cost re" ("soap" pause "of" pause

"and cost re";

and again in line

five, with an even more complex irregularity: the continuation of

"retainment" from the previous line in "tainment", followed

by two spaces, then "no" followed by two spaces, then "my"

followed by two spaces, then "sawdust" to end the line;

line six is even more

irregular: "wind" followed by two spaces, "or" followed by

two spaces, "soup's" followed by two spaces, "a" followed

by two spaces, "hand" followed by two spaces, to the line ending with

"ch", the first two letters of "chew".

All of these extra

spaces, some of which I have surely left out of this brief discussion, are

caused/required by the "block form" of the poems. All of this rhythmic

diversity or uncertainty, chaos or polyrhythmic potential, however one

experiences it, or choose to experience it, is generated by the constraints of

the block form. The limitations of the form insist on a degree of complexity

which would be unattainable without those limits. Without the constraints of

the block form, the spacings would be regular, as usual, and the rhythmic

complexity -- confusion -- indeterminacy -- instability -- etc. would be

entirely unnecessary.

Page 13

quacked the

picture

I think this was

originally, if only in the poet's mind, "cracked". Why do I think so?

Semantically, what difference does it make? I am not trying to make sense of

this poem by combining and recombining denotations. I am trying to understand

how it came to be what it is. How did it get into its shape? How did its words

get in their sequences and juxtapositions? What decisions were made by the

poet? Why were they made, to the exclusion of all other possible decisions? The

word "quacked" is not in this poem because of what we can find out

about it in a dictionary. It is here because of certain sonic and letteral

relationships it has with other words. In this specific case, I think the

decision to write "quacked the picture" was made because of how it sounds,

and because of how its letters are arranged -- in relation to the word

"cracked", which isn't in the poem at all. However, without the word

"cracked", which I am neither reading nor seeing as I look at and

read this poem, this poem could not be. It is a cracked poem, and the crack is

between what is, and what is behind what is, as a causal agent. And, in the

case of this poem, what is behind what is, what is behind this poem being the

poem it is, with its specific shapes and sounds, is the poet's mind -- making these

decisions, adding this to the stock of available reality.

thumb clam sorta br

inked and saw my b ack glivered with a

I think this was

"blinked". The poet thought or read "blinked" and decided

it would be better as "brinked". Why do I think so? Do you agree with

me? If not, why not? How can it possibly matter if the "thumb clam"

blinked, rather than brinked? What matters, to me, is how a poem becomes a

poem. Why this word here, and that word there, rather than any other words? Why

this letter, instead of that letter, why one letter replacing another? A poet

cannot write a sonnet without asking and answering these questions. Why should

a poet make a "block poem" without asking and answering them? What if

the subject of a block poem is the need for asking and answering these

questions? If that is the case, then it might be important for block poems to

insist that a reader notice these options and decisions.

I think

"glivered" was "silvered" before it was

"slivered", one step at a time to its present state. Why

"silvered"? Silvered because mirror.

melting mirror gn

itlem

This "gn"

was previously "on". The "g" retains (almost) the shape of

the "o", with the addition of a loop below the baseline. Where did

"itlem" come from? From "item"? From "them"? From

"it them"? "It item"? I don't know. Maybe it didn't come

from anywhere. Maybe Bennett invented it, ex nihilo, cut from the whole cloth

(rather than from a source text), conjured from the swarming sets of possible

combinations available to his mind. I don't think I am going it on a lem by

suggesting such a thing.

On page 72 is a

seven-line block poem entitled "os". The word "os" appears

in the center of the fourth line, in boldface.

In English os = bone

in Portuguese os = the in Spanish os = you

in French os = bone

in French nos =

our

in Portuguese nos - we in Spanish nos = us

in Portuguese noso =

we do not

also, in an earlier

note on my response to his book entitled Nos, Bennett mentioned connotations of

"breath", as in nose

The first three lines

and the last three lines are identical. no no no no no no

Line four is

significantly different:

no no n os o no no

So, the poem begins

for our reading, which is distinct from how it begins for our looking, as

follows:

o no no

and it ends

like this: no no n [no non]

It appears to be a

poem made entirely of negations, but it manages to negate itself, to affirm

itself, that is, which is a negation of its negations. Its initial reaction to

itself, in the center of itself, is "o no". And it's final statement

on itself, also at the center of itself, is "no non". We find

ourselves in this

kind of situation over and over, going about our daily lives. In order to

arrive at our quiet, nuanced affirmations, we must surround ourselves with

small, incessant negations. I only have to think for a moment of love, not the

idea of love but the daily experience of love, to be reminded of how this

works. This small poem, made of 40 'no's, an "os", an 'n' and an 'o'

-- is a love poem. A lyric poem, a love song, something very much like a sonnet.

On page 82 is

"lint", also known as "fork lint". Fork lint is one of the

secrets. Bennett has been known to mail and hand out name tags which read:

Hello, my name is Fork Lint. One wears such a badge like one of the Secret

Masters of The World!, one whose name is secret (perhaps hidden behind the mask

of Karen Eliot, or or some less familiar pseudonym), whose secrecy is open,

whose mastery is a ritual in a myth. The myth. Fork itself is one of the open

secrets. Lint is another. It is 2018 and still very near the beginning of the

Trump Regime. Science has come and gone and come back again as a semi-reliable

set of epistemological procedures. Poetry remains the guardian of the secrets,

and poetry has no more time for the sad academic pastime of hiding secrets in

places other than plain view. The fork is the fork, wherever you find it. Lint

is ever lint. Lint and fork together are, to quote a rubberstamped koan on the

cover of a recent envelope-zine from Bennett (if the mail box is the museum for

certain underground visual artists, then it is a library for certain poets in

the network): TINE : WAR. We are there. In the cosmic war against awareness,

every moment of awakening occurs at a fork in a road. We choose both/and, carry

onwords as our multitudes, swarming to the futures. Lint is wherever we have

been, following us, like a poem about to happen, whenever we awake.

The poem

"lint" (aka "fork lint") has seven lines. Lines one through

three and five through seven are identical:

fork fork fork fork

fork

Line four is:

fork fork lint fork

fork

It is to be chanted,

silently or aloud, a muttered mantra, neoist code for presence, the mirror in

the mask of what is.

Beginning on page 136

are twelve pages of "cut blocks", seven-line block poems in which the

central, fourth lines are much longer than than the surrounding six lines. On

page 143 is one entitled (using the fourth line as the title) "what you

scattered in the muddy shower". Here are the first three lines:

the gristle luggage

of my coughing suit it's seeing

It is hard to read

that, as it is, one word after another, on the page, only the letters that are

there, and only in the sequence in which they are written. "The gristle

luggage" becomes "the gristle language", I'm not sure why. Maybe

this book has destabilized the identity of the reader, not necessarily this

reader -- or not only this reader -- but the reader in general, the idea of the

reader. At every intersection there is a question, a set of questions, bandits

lying in ambush to attack any unprepared reader. To attack any prepared reader,

for that matter. I feel that I am not expected, maybe not permitted, to settle

on any certainty, to settle for certainty itself. The gristle language, I am

chewing on it "as we speak", the thistle language, the whistling

language, the language bristles. I bristle, chewing on these thistles,

whistling while we work, on the gristle language of my coffin. It is not far

from coughing to coffin, no matter which tine you take at the fork in the

reading road. What you (or I) scattered in the muddy shower? So far: language

thistles whistling bristles coffin. Am I making this up? Of course I am. Am I

inventing this way of reading, based on nothing, freely associating simply

because I can? I don't think so. Here are lines five through seven:

with his footwe ar

mament cut ting off his ankle

What is is as rich as

we will permit ourselves to make it. It is part of the job of the poet to

assist us in knowing that. With his foot we are. With his footwear armament.

With his footwear armament cut. With his footwear armament we are cut. With his

footwear armament we are cutting. Cut one make two cut thirty two make sixty

four cut five hundred and twelve make a thousand and twenty four on and ongoing

make a world make a cosmos a life.

03.13/14.2018

__________________________________________

Postscript

Email exchange between Bennett &

Leftwich, 03.14.2018

JMB:

couple typos i saw:

top of p. 4: "Page 7" should be "Page

13"

2nd to last parag. p. 5, line 2: It's initial reaction... should be:

Its initial reaction...

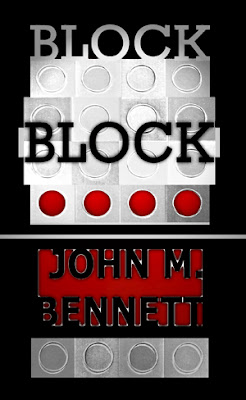

Fascinating

essay/engagement with this book! I think that when/if this is published, scans

of the poems you discuss from the book could be included, so it's clear what

you're talking about. Re the poem on page 13, the line "melting mirror gn

itlem": "gn itlem" is also "melti ng" backward. This

in no way detracts from what you say about it as read "forward",

which is obviously the way it will be read, primarily!

Re the

translation of "noso" as Portuguese "we do not": though I

found this definition, as you did, via an internet translation site, it's not

something I've ever read or heard. Maybe it's some

archaic

usage? Normally, "we do not" would be "nós não".

"noso" means "our" in Galician, similar to Portuguese,

which has "nosso" for "our" (used with a male noun). Bottom

line is that the phoneme "nos" has an enormous sea of swarming

resonances, as you rightly point out. And your conclusion that this is a love

poem is exactly right, and right in large part due to such swarmings.

The

phrase "fork lint" was created by Cathy and me collaboratively. Forks

and Lint are both topics/talismans we have played with extensively in lots of

different ways. I like the phrase a lot, it makes a great mantra, tripping of

the tongue in rivers of sound... And in that regard, these poems, especially

the ones with repetitive words, are great performance scores as well as visual

mandalas (of a sort) - mandalas that move through time, like poems, but are

also static, meant to be perceived all at once as single objects.

forklinttnilkrof,

thank you!, john

JL:

thanks, John.

fixed the typos.

and now that you mention it, it is obvious what

this is!

gn itlem

melti ng

it amazes me, what i see and what i don't see when

reading your work. it seems like this backwards melting is so obvious, now that

i see it.

should have been obvious.

anyway, i agree, if this is ever published

scans of the poems should be included.

the

internet as a whole is not reliable at all for translation. i have been

learning and relearning that over and over in the last year or so. i thought it

had gotten better than it is.

JMB:

problem is, that language is so immersed in context, that what a word

"means" is not a fixed thing at all, ever. and language is always

changing, constantly, and much faster than one normally realizes

JL:

that's a good "problem" for us not so for our machines

over

time these machines will teach us, collectively, to be limited in the same ways

that they are limited

JMB:

hah! unless the machines all fail when the power grid collapses....

*****