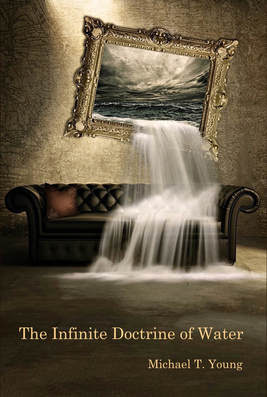

The Infinite Doctrine of Water by Michael T. Young

(Terrapin Books, West Caldwell, N.J., 2018)

The

close observer of briny passages

Hunt only at night. Fly erratically.

Defy even your own expectations.

So opens The Infinite Doctrine of Water, Michael

T. Young’s third collection of poetry. Like the red-letter passages of the King James Bible, “Advice From a Bat,”

containing these lines, is hair-raising, and yet it offers far more than it

demands.

Young’s poems are often metaphysical algorithms, not meant to

entertain you as much as to prepare you for passages through straits you may

not yet have imagined. In this sense, his collections are the Belfasts and La

Spezias of poetry, fitting out readers for intellectual and spiritual voyages.

And yet these journeys are often around the corner, in microbial

empires of intuition, reminding us again and again that poetry is a voyage into

infinity, and that a culture like ours that is always writing its obituary is

afraid of something deep and close, a truth that a poem out of nowhere may

discover.

Take this penultimate stanza from the last poem, “The Voice of

Water”:

When it whispers, it whispers with

the same heaping hush of salt

pouring from an uncapped shaker.

I regard this stanza as perfect in the way Glenway Westcott’s

novella, The Pilgrim Hawk, is perfect. And in both

instances—Westcott was a poet, too—there is something in the pristine

excellence of the work likely to chill those politicians and critics who are

most full of themselves.

Young is a poet of near-perfect prosody—who can attain

perfection?—a formalist in whom the interplay of observed information and

formal versification fulfill the true purpose of alchemy, which is not to turn

base metals into gold, but to ennoble humanity.

That kind of alchemy requires the indisputable elixir, and for

Young that elixir is very close to angelic. He is such a refined, such an

astute observer of least things that we are always reminded of Hebrews 13:2,

entertaining angels without realizing it. We would expect an angel to celebrate

grandeur in least things, just as Jesus jolted the ancient world by saying how

hard it would be for a rich man to enter heaven.

The Trojan Wars, the founding of Rome, these are grand

subjects, calling for a Homer or a Virgil, but a tree growing in Jersey City, a

paperclip, the moods of the Hudson’s tides—these require an intellect and eye

so respectful of the ordinary that its underlying assumption becomes that

nothing is ordinary:

It’s a day when one can hear

the morning glories growing,

Who

is Michael Young’s intended hearer? In the case of most poets we usually assume

an abstract entity called a readership, an audience. That’s what marketers

assume. It’s what editors have to assume. But Young’s poetry is much too

companionable for that. When you read one of his syllabically precise poems

you’re walking down a street with him, chatting in a café. You’re confiding in

each other. The poems are interlocutors, that’s how intimate they are:

Every day I have to decide when to cut over

to Broadway, as if choosing a theme,

maybe the expedient dash up Fulton Street

bordered by the iron fence of Saint Paul’s Church,

gravestones blinking through the posts.

The reader feels moved to respond, and the cadence and rhythm,

whether blank verse, tercet or quatrain, is as inviting as knowing the quirks

of an old friend. That’s the genius of Young’s metrics. They instill a kind of

echolalia. They’re not meant to impress, they’re meant to share, like familiar

tools. If you’ve loved someone who exhibited echolalia you’ll know what I

mean—in sheer delight you’re inspired to repeat what has just been said.

Like Wallace Stevens, whose work Young’s sometimes recalls, this

poet is keenly aware that the peripatetic mind is always keener and more

adventurous than the peripatetic foot.

The sin of Michael Young’s poems is to

dwell among the sights and sounds and sensations that society is designed to

rush on by and ignore for fear of being told its premises are all wrong.

The Infinite Doctrine of Water is the exquisite witness of a superb

young poet to a world continually refreshed by the briny crosscurrents of New

York Bay and the Hudson estuary.

*****

Djelloul Marbrook

is the author of seven books of fiction and nine of poetry, including Far

from Algiers (2008, Kent State University Press), winner of the Wick

Poetry Prize and the 2010 International Book Award in poetry. Three more books

of poetry and the fiction trilogy Light Piercing Water are forthcoming

from Leaky Boot Press (UK) in 2018-19. A retired newspaper editor and reporter

and a US Navy veteran, he lives in the mid-Hudson valley with his wife

Marilyn.