Interview with Denise Newman about her book Future People (Apogee, 2016) by Norman Fischer

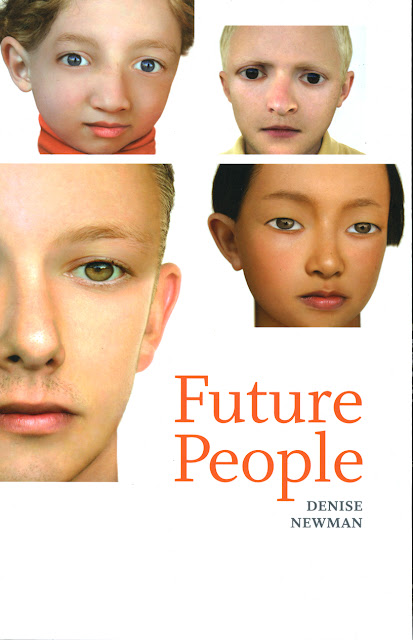

NF: In the title work, “Future People,” you are reacting to the

photographic portraits by Gigi Janchang from her series Portraits: 2084.

Your poem is pretty intense and repeats the phrases "a moral

structure" and "in reality" which take on resonance and urgency

with each iteration. There also seems to be some kind of theology going on

here. Can you shed some light on, first, how these (to me) weird pictures relate

to the poem, and, second, if possible, what you intend in the poem?

DN: The poem is in collaboration with Gigi. She photographed dozens people, and then collaged single features to

create new faces. As I was writing my poem, she began creating younger

portraits influenced by my take on them. I was curious about what made these

future people slightly creepy. Their eyes are wet and lively, but they seem

stuck, as though trapped between life and death. I decided to set them in

motion to see how they’d function in life, and if there was any hope for them.

At some point in the writing, I realized that what was missing was the glue

that holds all the features together, what some might call a soul.

Lazarus arrives mid-way in the poem to help. He’s been dead, so he

understands their situation, and he patiently tries to put them in reality, not

by teaching them a moral code, but by showing respect and kindness. He knows

he’ll fail, but still he tries to help. If there’s a theology here, it’s in Lazarus’s actions, which are not situated in fear, like

the moral code, but rather, compassion—a meeting.

“He knows he’ll fail.” Probably true, but sad. Is it Lazarus who is

speaking these lines:

“A bell stuffed with newspapers won’t ring,

that’s how it is, but I hear things, for shame,

hear them discussing the removal

of so and so, in a tone of it’s done already,

but I object or, I, object,

cried on my sock and it got wet”

I love this passage, for its complexity (“I object, and I, object”

seems like the problem in a nutshell) and its precise analysis of our moment

(“A bell stuffed with newspapers can’t ring”). What about the use of the word

“shame” here? Is Lazarus, are you’re we all, ashamed because “we know we’ll

fail?”

That’s actually the female future person speaking.

Lazarus is encouraging her to describe her experience; she’s been mute, but

paying attention to the violence around her. She objects to it, and yet she’s

stuck as their object. Sad as the moment is, Lazarus is having a little success

here with her.

This is about the book’s opening series of short poems, which seem to

enact the often terrible and always interesting limitations of language. I’m

homing in on two lines from the poem SHADE:

Pick a word or two from its

interior air: ERROR

MIRROR

In light of your idea of soul as glue, that holds a life together as

real (from your first answer) what does language have to do with it? That is,

is this series telling us something about the relation of ‘soul’ to ‘language?’

Your question makes me see a connection between the short, torqued

poems and the future people, whose faces have the same effect as the words

ERROR MIRROR. They both attract and repulse because they’re only slightly off.

You find the same magnetic incongruence between language and phenomena, and the

finer the articulation the more charged those gaps seem. The future people have

adapted to being illusory and their language reflects this (empty speech or no

speech at all). Lazarus goads them to say what they’re really thinking so that

maybe they’ll understand what’s imprisoning them. I think language is an

essential limb of consciousness that we need to keep track of and nourish.

In a way, I was a future person writing the short poems, as I was starting

over with poetry. After writing “The Book of Thel,” I felt emptied out and

stopped writing. I began making videos where I worked with other elements, like

ants and snails, to put simple phrases in play, such as “in no way.” When I

returned to writing a couple of years later, I started with strange words and

their etymologies, like barbican and futtock, and ordinary words and their

surprising etymologies, like “autopsy,” meaning

“to see with your own eyes.” I was returning to the mysterious depths of

language, which means returning to the mysterious depths of being a human.

“Mysterious depths,” yes. Maybe it took not writing for a while to get

to that, your “being

emptied out.” Which brings me to my next

question, about “The Book of Thel” series, which I find, yes, quite intricate.

I can see how it might have worn you out! Your photo preceding the poem —of a

woman walking on a stone labyrinth on an open plain— rhymes with Blake’s poem

by the same name: a young women (Thel) full of questions setting out from

innocence into the impossible world. I know you have a daughter, Eva, who is

just on the brink of such a journey. Though the poem’s tone is easy, it seems

to evoke insolvable problems particular to the feminine— though I am not sure.

What was your impulse in writing it? Also, one of the poems in the series is

dedicated to Leslie Scalapino our mutual friend, whose life was possibly also

such a journey. To what extent does her work inspire the poem?

That’s a photo of Eva. She’s the main inspiration for Thel. When she

was in the third grade she told me she didn't want to progress any more—she

wanted to stay right there at that age. I became curious about the

transition she was sensing, and it got me thinking of Blake’s poem, where Thel,

a girl living in eternity, becomes interested in the mortals and decides to go

experience life on the other side. I used Blake’s poem as my reference point,

and followed a similar trajectory of a young woman coming of age, but in a

contemporary setting. The objectification Thel experiences, in a job interview

and elsewhere, is exactly what’s coming to light now, and may be what my

daughter was sensing—the world of deception and exploitation awaiting her.

Leslie Scalapino has had such a tremendous influence on my writing and

thinking, it’s hard to put a finger on any one thing (though sticking a

dedication in the middle of a series is something she’d do). Her fierceness to

name falsities, especially hierarchies, is a strong part of this. She wrote to

discover reality for herself. Her thinking and discovering is in the whipped up

syntax, which is why it was so mesmerizing to hear her read. I often think of

her phrase, “the self is a guinea pig.” It’s one of my guiding principles.

Leslie died as I was writing Thel. I had a dream about her a month

after her death, and then wrote that section you refer to. She becomes another

guide for Thel, enabling her to be spontaneous with her emotions, and also to

recognize what does not die—everything unborn.

This question is about the section of short poems that follows The

Book of Thel. Since Nov 9, 2016 (Trump election victory) it

seems the poetry world has been obsessed with response and resistance. Although

the poems in this section were written before that, they seem pointedly political,

but differently. I want to zero in on the final poem in the series, Patience Is

To Suffice.

It’s the relationship between the void and avoid

old monk and donkey—

An animal kicks its itch and the artist says

“at this point we could go toward

utopias or total destruction.”

It’s that moment of hesitation

at the exit marked exist.

You seem to be claiming a particular sort of politics for the artist.

Can you say more about that?

Now

that you mention it, there might be a political mode suggested here. “Patience” is a key word—what Obama often called for—slow

change. But there needs to be a diversity of expressions/visions, infiltrating

all sectors of society for lasting change to occur, and poetry is particularly

necessary now because it invigorates the main tool of politics —language—with

imagination.

A

few years ago I started feeling frustrated with the marginalization of poetry

in the US. I attended a lecture by the social practice artist Harrell Fletcher,

and was struck by the generosity of his work. It made me wonder if poetry could

have a similar civic engagement, and so I began experimenting with taking

poetry off the page. In 2015, I received a grant with my friend and colleague

Hazel White to do a large-scale poetry project at the UC Berkeley Botanical

Garden. We decided to engage the staff and visitors to create a humungous index

of all the language that we could capture plus images. In a way, we were doing

poetry live with others, on guided walks and during our weekly open studio. We

asked slanted questions like, “what do the fences not keep out?” and showed

them our bits of research without packaging it up neatly. People said amazing

things, and often seemed surprised by what they were saying. Now I see that I

need both kinds of work—individual, contemplative writing and direct public

engagement (what Octavio Paz called fiesta)—to integrate my roles as artist and citizen.

The last poem in the book, Midsummer Day, evokes Bernadette Mayer's

classic Midwinter Day. Your poem

(four pages long, and evoking "events" of a single clock day) begins

with a quotation from David Bohm, "Time is a theory everyone adopts for

psychological purposes." Time fascinates me too, I seem to write about it

constantly. How does your poem enact (if it does) Bohm's theory of time? And

how do you see this in relation to Bernadette's poem?

Midwinter Day is an important work for me. I learned from Bernadette

Mayer how to write intimately about domestic life, so helpful when our daughter

was young, and also to use time as a form. There’s a poem in my first book that

compresses a whole lifetime into the 24 hours of a day—each hour, a stage of

life. My title, “Midsummer Day” is a nod to Mayer’s book, though I wrote the

poem on that day because it’s my birthday and what I asked for as a gift from

my family—24 hours to write. I’ve done it three years in a row, starting at 5

am, and ending at 4:59 am. It’s a way to get off the grid of time and

experience a complete day from another angle. I easily fall into routines or

feel anxious about time, how I’m always behind. It’s good to step back to realize

how our perception of time is largely made up. All we have is time—we are time,

as you write in your interpretation of Dogen’s essay on time in Magnolias

All At Once, “There is no time other than being, and no being other than

time, and no time other than the time being…at least for the time being.” I

need to recalibrate constantly to experience this.

Amazing: a birthday gift of twenty-four quiet hours to write. Yes, a

gift. As is this interview, thanks Denise.

Thanks, Norman. It’s been a pleasure.

Denise Newman's other poetry collections are The New Make Believe,

Wild Goods, and Human Forest. She is the translator

of Azorno and The Painted Room, both by the

late Danish poet, Inger Christensen, and Baboon by Naja Marie

Aidt, which won the 2015 PEN Translation Award. Newman is also involved in

video, installation, and social practice projects that explore language and

poetics. She teaches at the California College of the Arts.

Norman Fischer is a poet, essayist, and Zen

Buddhist priest. The latest of his more than twenty-five prose and poetry

titles are the just-out serial poems Untitled Series: Life As It Is (Talisman

House) and On a Train At Night (Presse Universite de Rouen et

Havre). His latest prose works are What Is Zen? Plain Talk for a

Beginner’s Mind, and Experience: Thinking, Writing, Language and

Religion. He lives in Muir Beach, California.